Remember Acid Rain?

How Cap-and-Trade Solved an Environmental Catastrophe & Insights on Today’s Carbon Markets from the “Father of Carbon Trading”

In the 1980s and '90s, you couldn't open a newspaper or turn on the TV without seeing headlines about Acid Rain and its detrimental environmental effects. Its implications were far-reaching. Delicate aquatic ecosystems were disrupted. Building and infrastructure deterioration was accelerated. New health risks emerged as respiratory issues increased and water became acidified. This was the preeminent environmental concern of its day. Yet, the problem has mainly been relegated to the history books, especially in more developed economies of North America and Europe.

According to the EPA, Acid Rain results when sulfur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxides (NOX) are emitted into the atmosphere and transported by wind and air currents. The SO2 and NOX react with water, oxygen, and other chemicals to form sulfuric and nitric acids, which then mix with water and other materials before falling to the ground.

The reason you don’t hear about Acid Rain as much today is because the problem was largely mitigated by implementing cap-and-trade programs that put a price on industrial SO2 and NOx emissions. These systems' effectiveness relied on creative engineering to apply free market principles to something that had never been done, coupled with the determination to overcome the legal and regulatory hurdles. A large part of the success of these cap-and-trade programs is due to Dr. Richard Sandor, an early champion of using the free market to solve climate issues.

Today, with Acid rain consigned to history, the bigger, broader, and more complex environmental problem of climate change has taken center stage. The modern climate issue is driven by unregulated industrial emissions of greenhouse gases, primarily carbon dioxide (CO2). Many people don't realize that similar cap-and-trade programs that were applied to Acid Rain are now being put to work to address climate change – and Dr. Sandor is still playing a pivotal role in championing cap-and-trade in the form of emissions trading systems worldwide.

We had the honor of hosting Dr. Sandor at our recent institutional carbon roadshow event in Chicago last month. Here is what Dr. Sandor had to say about the cap-and-trade system that may solve our most significant environmental challenge.

Who is Dr. Richard Sandor?

Dr. Sandor has been a pivotal figure in the evolution of the emissions-trading industry. During the 1970s, as the chief economist for the Chicago Board of Trade, he was instrumental in creating the financial futures market, earning him the title "Father of Financial Futures." He extended his experience with futures into the creation of environmental exchange-traded products, first with SO2 and NOx credits and now with Greenhouse Gases and CO2 credits.

He spearheaded the launch of both the Chicago and the European Climate Exchanges, where companies can trade carbon credits. His contributions have been invaluable in shaping the landscape of carbon trading and environmental markets, recognized by TIME Magazine as a "Hero of the Planet" and later as the "Father of Carbon Trading." It was a privilege to have him share his insights and expertise at our event.

Cap then Trade: From Doubt to Miracle

By the late 1980s, people started to recognize that Acid Rain was a serious issue that could no longer be ignored. Although some politicians and certain environmentalists initially clashed on how best to solve it, they ultimately agreed on the market-based cap-and-trade program.

At first, there was skepticism about the effectiveness of the program, that it would put US industry at an economic disadvantage and cause electricity prices to skyrocket. The price of sulfur dioxide (the main component in Acid Rain) was forecasted to trade in the $300-900 per ton range, potentially costing billions.

Despite these concerns, the SO2 and NOx cap-and-trade programs were rolled out broadly, and rather than cause economic calamity, they worked. Eventually, Acid Rain dissipated in the US completely. According to an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) study, the estimated benefits of the SO2 and NOx program exceeded the costs by a factor of at least 30 to 1 over the observed period of 1990 to 2020.1 Although there was some initial pushback, it quickly became widely regarded as an environmental success story for effectively reducing acid rain.

How did they arrive at cap-and-trade, and why is it so effective? Dr. Sandor retold the early history of implementing cap-and-trade and how the program's design naturally benefits the environment, politics, and business.

Free Market Principles to Encourage Cost-Effective Decarbonization

Ultimately, Congress was persuaded by the affected entities, economists, and environmentalists that the market-based approach was the best way to proceed. The Republican-led Bush administration also called for the most ambitious of the potential SO2 reduction targets scenarios under consideration, a 10-million-ton reduction from the 1980 baseline (equivalent to an overall 50% cut in emissions),2 largely because of their confidence in cap-and-trade. Interestingly, support for this market-based solution was not divided along party lines but instead was viewed as a strong bipartisan tool for achieving climate goals.

The program was rolled out in two waves: the first phase included 445 mostly coal-burning electric utility plants starting in 1995, and the second phase, which began in 2000, introduced smaller units fired by coal, oil, and gas for a combined total of over 2,000 compliance units.3 In just the first year the cap was set, emissions fell by three million tons, way ahead of schedule.4 By 2007, the 8.95 million cap was reached, and by 2010, emissions declined by an additional 5.1 million tons.5 At the same time, the implementation of pollution control technologies like scrubbers, which remove SO2 from the exhaust by passing it through an alkaline substance, became feasible thanks to the savings achieved from avoiding the cost of emitting SO2 under the cap-and-trade system. Furthermore, regulated entities were nearly 100% compliant, largely thanks to the program’s inherent flexibility.

Sandor highlighted how cap-and-trade encourages regulated companies to find the most cost-effective strategies for their business while accelerating innovation within the overall industry. It works well because it doesn't dictate how companies should reduce emissions. Instead, a declining cap keeps emissions in check while regulated companies can fulfill their compliance obligation on their own terms. Some companies chose to install scrubbers; others switched to more low-sulfur coal, which became available through a new mining technique. Because companies could bank their allowances or sell them for profit, it further incentivized reducing emissions beyond their compliance obligations.

As Sandor put it, the effectiveness in this model lies in its relative effeciency. Cap-and-trade creates an environment that allows the private sector to have the flexibility to navigate emissions abatement options under the parameters of the regulators' market rules, all while delivering considerable emissions reductions and accelerating innovation through the most cost-effective means.

The innovation in the 1990s stemmed from private sector incentives to minimize costs. In the twenty-first century, much like other financial markets, emission credit markets have evolved, too, contributing to green tech development from auction revenue. In California, $11 billion from carbon credit sales have been designated towards half a million projects that fight climate change and cut pollution since the program’s inception. Another $17 billion raised from the sale of carbon credits has been reserved for larger housing and transportation initiatives to combat state carbon pollution.6 The benefit is twofold. Private firms want to minimize costs by investing in the development of cleaner operations while the government directs new revenue from the carbon market to lower public emissions. A similar use of carbon market revenue is seen in Europe, where raised capital is invested in the EU Innovation Fund.

Patterns of Financial Innovation

According to Dr. Sandor, financial innovation is a 20-to-40-year business. The timeline starts with 0-2 years in its infancy idea stage, then 2-5 years in 'high school,' 5-20 'young adult' years, and finally reaches full maturity during the 20-40 year phase. This understanding is important because, according to Sandor, we are only roughly 19 years in for carbon markets. He reminded us that it was 30 years ago at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio—the first UN environmental conference—that carbon cap-and-trade was first introduced, and then, five years later, it became a policy adopted by the UN during the Kyoto Protocol. Financial innovation does not happen overnight but is instead built up through an evolving process. Only roughly a fifth of global emissions are currently covered by cap-and-trade programs, yet we are seeing an expansion of existing markets and a mushrooming of planned new market launches.

Carbon Big Bang: China

Sandor believes the big turning point will likely come with China. His optimism for the country stems from its history of rolling out new, innovative technologies at an impressive speed. For those who are not familiar with China, he explained how "it looks like they do nothing...they do nothing...and then all of a sudden there is a high-speed rail from Shanghai to Guangzhou." In just over the course of a decade, China's high-speed rail network expanded by 20,000 plus miles. Now, the length of their high-speed rail network far surpasses the rest of the world's combined.7 Not to mention, China rapidly became the largest market for electric vehicles, representing 60% of global EV sales.8 According to Sandor, it's this kind of stealth rollout of technology and innovation that may take the world by surprise.

While working in China, Sandor spoke with students at Beijing University. He was impressed to find that they had a cap-and-trade club for nearly ten years. Although China is still navigating its own national ETS and pilot programs, he stated that China's top students are sometimes more well-versed in the global carbon markets than top universities in the US, which are only just starting to offer classes on the subject.

Sandor often likes to refer to the Economic Kuznets Curve, which illustrates the inverted U-shaped relationship between economic output per capita (growth) and various measures of environmental quality. He explained that it is basic "caveman economics" that people will spend more on environmental goods once their basic needs are met. As developing countries move further along this curve, more attention is given to environmental initiatives, as is becoming increasingly the case in China. Currently, China’s carbon market covers just over 40% of the country’s total emissions but holds robust growth potential as it continues to evolve and expand.9

Source: KraneShares

Environmental Markets Attract Greater Open Interest Than Gold

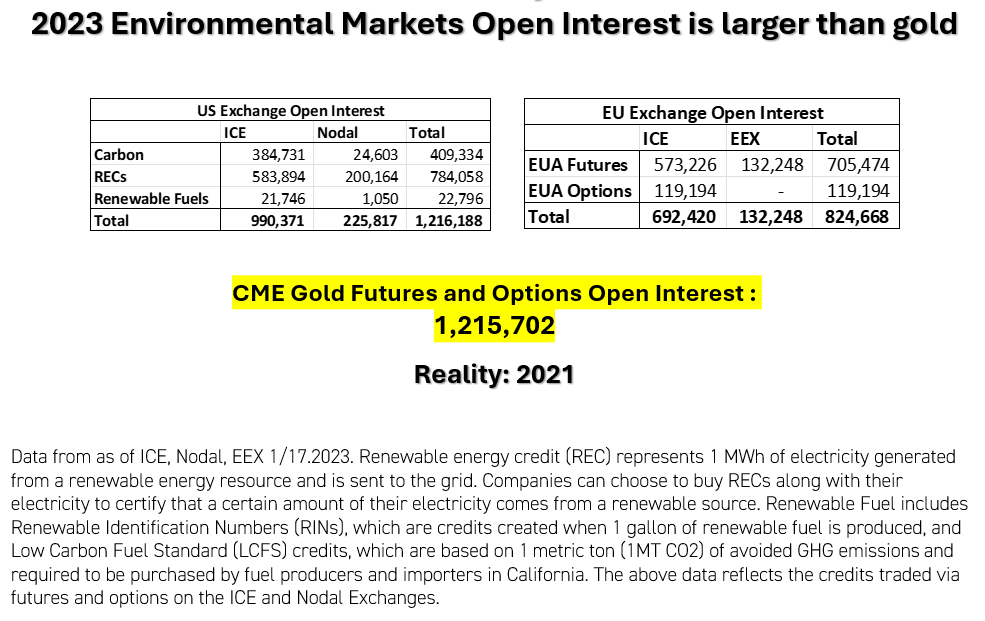

Dr. Sandor wrapped up the session by reflecting on how to approach environmental markets, including carbon, from an investing perspective. Despite any misconceptions, these are real, sizable markets that are part of a rapidly growing global financial trend. To put these markets in perspective with traditional commodities, Sandor highlighted how the combined open interest of US-based carbon, renewable energy certificates (RECs), and renewable fuel futures and options contracts are greater than that of CME gold contracts. Similarly, European carbon contracts' open interest is just slightly under that of gold.10

He further explained the importance of not letting your judgment be colored by problems identified with Environmental Social Governance (ESG) trends. Dr. Sandor explained that carbon is not an ESG investment but rather a purer play on climate impact, where investors can help directly support liquidity and price discovery in these markets.

Regardless of your beliefs on climate change, he emphasized that investors "would be unwise to short environmental products." Carbon allowances and the greater environmental financial space are part of a massive secular investment cycle driven by the world’s focus on the energy transition. Companies and, in turn, investment portfolios are increasingly becoming more exposed to the rising price of carbon as climate change poses an increasing effect on risk profile.

How Investors Can Access the Global Carbon Markets

We appreciate Dr. Sandor taking the time to speak at our event and putting the history of cap-and-trade into perspective. The confidence he exudes for the future of cap-and-trade can only come from someone who has seen these markets grow from an abstract idea to widespread adoption worldwide.

From its origins in Acid Rain, carbon cap-and-trade has now expanded to a global scale to tackle the much bigger problem of climate change. The largest, most liquid of these markets are the European Union, California, the United Kingdom, and the Northeast US Power generation market. By allocating to these markets, investors can create impact through supporting liquidity, price discovery, and funding green initiatives. For streamlined access to these markets, the KraneShares Global Carbon Strategy ETF (KBRN) provides global exposure to the four largest markets. The KraneShares California Carbon Allowance Strategy ETF (KCCA) and the KraneShares European Carbon Allowance Strategy ETF (KEUA) offer a more tailored exposure to specific markets. Investors may benefit from risk-adjusted returns and impactful investment allocation in carbon credits, helping to relegate Climate Change to a notion of the past, like Acid Rain.

For KRBN, KCCA, and KEUA standard performance, top 10 holdings, risks, and other fund information, please click here.

- EPA, "Benefits and Costs of the Clean Air Act 1990-2020, the Second Prospective Study," https://www.epa.gov/clean-air-act-overview/benefits-and-costs-clean-air-act-1990-2020-second-prospective-study

- US Environmental Protection Agency, “Acid Rain Program,” retrieved 6/15/2024.

- US Environmental Protection Agency, “Acid Rain Program,” retrieved 6/15/2024.

- Smithsonian Magazine, “The Political History of Cap and Trade,” August 2009.

- Robert N. Stavins, Richard Schmalensee, Harvard Kennedy School, “The SO2 Allowance Trading System: The Ironic History of a Grand Policy Experiment,” August 3, 2012

- Data from the California Governor’s Office as of 05/08/2024

- CGTN, “From nobody to somebody: China's high-speed rail in numbers,” October 1, 2020.

- IEA, “Tracking Electric Vehicles,” https://www.iea.org/energy-system/transport/electric-vehicles.

- ICAP, “China National ETS,” retrieved 4/25/2024

- Data from ICE, Nodal, EEX as of 12/31/2023. Carbon, RECs, and Renewable Fuels represent futures and options contracts.